A bridge, a lock, a solo wanderer in Rome

Ponte Milvio Bridge, Rome. Photograph: Kiki99/Flickr

I lost count how many times I crossed the Tiber River during my five days in Rome. I went from ancient site to ancient site, over footbridges and hulking stone viaducts—always walking, sometimes in the rain, often under an autumn sun. On the way to St. Peter’s Basilica, I crossed Ponte Sant’ Angelo, built for Hadrian in AD134 and many centuries later a popular execution site. I trudged over Ponte Sisto after leaving Trastevere, soaked to the toes from an afternoon storm. I was not quite lost, although not exactly sure where I was going. The Tiber zigged and zagged, as if drawn by a drunken cartographer, but there always seemed to be a way to get to the other side. If I missed this bridge, I knew there would be another nearby.

I came to realize that Rome can be a difficult place for a single person to visit. Everywhere you encounter couples strolling along, shopping bags slung over their linked arms, couples taking selfies in front of Trevi fountain, couples gazing up at one stunning ruin or another. Was the City of Love not enough for these amorous travellers? Must they have the Eternal City, too?

Soon I discovered I couldn’t escape them, even at the outer reaches of town. I’d heard about a bridge called Ponte Milvio, Rome’s oldest and a destination for the lovesick. In 2020, Federico Moccia published a novel in which a young couple fasten a padlock to this very bridge and throw the key into the Tiber below. The book, Ho Voglia di Te (I Want You), sold more than two million copies and was made into a film. Couples inspired by the story began to visit Ponte Milvio, fastening lock upon lock—so many that they broke two lampposts and threatened the bridge’s structural integrity. This ancient edifice—which had stood in one form or another for more than two millennia—was being assaulted by love.

I couldn’t deny the symbolic power of attaching small charms to a bridge, that feat of human engineering that provides safe passage, that unites two people. But wasn’t this whimsical form of vandalism a misguided public display of affection, like having a lover’s name tattooed on your arm where it would fade and warp with time? The locks would weather badly, I thought. If a relationship ended, the evidence would remain, rusted from the rain and there for all to see.

Wanting to see it for myself, I boarded Tram 2 near Piazza del Popolo and headed north. We creaked along, an arthritic metal caterpillar winding up a crooked road. The tourists grew fewer, the gelato shops vanished. I alighted near a park and got my bearings. Ponte Milvio is wedged between an unremarkable residential area and a four-lane thoroughfare. It is possibly the most unromantic spot in the entire city. City officials, concerned for the integrity of the bridge, had cut away the locks and declared the practice illegal in 2020, yet people still made the pilgrimage north. Not surprising, perhaps, given the bridge’s lascivious history: Nero once came to Ponte Milvio “for his debaucheries” and the historian Tacitus said it was “famous for its nocturnal attractions.”

Wanting to see it for myself, I boarded Tram 2 near Piazza del Popolo and headed north. We creaked along, an arthritic metal caterpillar winding up a crooked road. The tourists grew fewer, the gelato shops vanished. I alighted near a park and got my bearings. Ponte Milvio is wedged between an unremarkable residential area and a four-lane thoroughfare. It is possibly the most unromantic spot in the entire city. City officials, concerned for the integrity of the bridge, had cut away the locks and declared the practice illegal in 2020, yet people still made the pilgrimage north. Not surprising, perhaps, given the bridge’s lascivious history: Nero once came to Ponte Milvio “for his debaucheries” and the historian Tacitus said it was “famous for its nocturnal attractions.”

The day I visited was sunny and warm, and there appeared to be no gauche activities taking place. A young couple necked atop a gangway; teenagers gathered in the middle of the bridge to shoot the breeze. There was evidence, however, of recent activity. Padlocks ringed some of the lampposts, forming a kind of oversized charm bracelet, and hung from the base of the lanterns. Some people had purchased red heart-shaped locks and had them engraved. They were tacky, but charming.

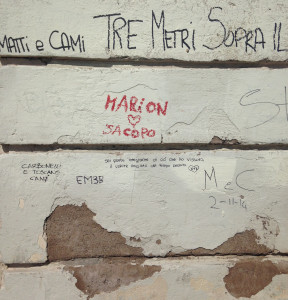

Last year, I briefly dated a friend and, anxious to know where it was going, I’d asked: What if this happens? What if that happens? What if we end up hating each other? He calmly said, “We’ll cross that bridge when we get to it.” Now here I was on a bridge covered by expressions of love. Someone had drawn a large cartoon heart with K + Z inside. Another had written, “Ti amo da impazzire [I love you crazy], L & C, 12/06/14.” And on a small blue door leading to a tower, I made out the very simple Marion ♥ Sacopo. Who was Marion and where had she found her Sacopo? Did she still love him? What had happened? Had they made it across other bridges since?

Despite the graffiti and the locks, Ponte Milvio itself seemed no worse for wear. If Garibaldi couldn’t destroy it, then how could something as innocent as love? I crossed Ponte Milvio alone, the sun still bright, and came across a man at the foot of the bridge singing karaoke to old pop tunes that he blasted out of a large speaker. He too was alone and he didn’t seem at all unhappy.

• This story is from the winter 2020 issue of Eighteen Bridges. Subscribe here.

• Based in the UK, Craille Maguire Gillies is features editor at Eighteen Bridges and works for the Guardian.

A bridge, a lock, a solo wanderer in Rome

No comments yet.