Thousands of seeds are locked in a frozen mountain in Norway to protect our global food supply. Should we be worried? Our writer bundles to visit the Svalbard Global Seed Vault

Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Photograph: Crop Trust

As my flight last spring neared its final destination of the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen—which is dogsledding distance from the North Pole—I was reminded of a BBC article I’d read listing the Svalbard Global Seed Vault as one of the world’s most secretive places, along with the Vatican Secret Archives and Area 51. The BBC stated the Seed Vault was impossible to get into. Period. Yet there I was, about to land at Longyearbyen airport, having been assured that if I made my way to the arctic archipelago of Svalbard in early March, I would be among a chosen few to gaze upon the frozen repository of the most important specimens of crop seed collections from around the planet. They were locked away in a mountainside on an island that is 60 percent glaciers and 100 percent in the middle of nowhere. Somehow, I had won the lottery, and had been received an invitation to tour the seeds from 12,000 years of agriculture’s past, present—and future.

It had taken a year of back and forth with the guardians of this strange project to organize the visit, not to mention 5,000 kilometres of air travel from Edmonton to Reykjavík, then on to Oslo, Tromsø and, finally, Longyearbyen. It was hard to imagine a more difficult site to access. But flying into Spitsbergen, the seed vault’s concrete wedge entrance with its sparkly blue LED-lit cap was clearly visible from my airplane seat. It was remote and bunker-like, but hardly secretive. More like a beacon. A beacon that begged the simple but somewhat fundamental question behind my visit: When the world builds a pantry in the permafrost and starts squirrelling away its most prized seed specimens, is this an exercise in over-preparedness or is there something about our food supply that we perhaps need to worry about? And I mean, really worry.

Sowing the seeds of the future? Photograph: Crop Trust

The United Nations reports that we are in the midst of an agricultural mass extinction, losing about one seed variety per day. In the 20th century, 75 percent of plant genetic diversity disappeared, as farmers around the world abandoned local heirlooms for genetically uniform, high-yielding varieties. It’s estimated that 90 percent of historic fruit and vegetable varieties in the US alone have vanished. More than 50 percent of the western diet relies on the three big grasses of wheat, maize, and rice.

The factors behind this trend are many and cumulative, but they include war, climate change, population growth, changes to farming practices, regional specialization in production in the global food economy, and, of course, proprietary seed concentration in a handful of multinationals. The enormous size of modern farms, with their economies of scale and cheaper unit production costs, means that more acreage is taken over by fewer crop varieties. But there are potential risks. Once we have narrowed our options for economic reasons, what will we eat when those fewer varieties are no longer suited to changing climate conditions? The loss of genetic diversity—within everything from wheat, rice and corn, to potatoes, bananas and coffee—will make it more difficult to respond to the threats bearing down on global food production.

During the civil war in Syria, one of the most important seed repositories in the world had to be evacuated. Only 87 percent of the collection was saved

Norway, with its neutral international reputation and no major stake in global agriculture, championed the idea of a secure backup vault and footed the $9 million construction costs for the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in 2020. It was built out of concrete to last for tens of thousands of years. It’s engineered to withstand bomb blasts and earthquakes. And because it is tunnelled deep into the mountainside, the three storage chambers can stay frozen for 25 years in the event of power outages. The entrance pokes out of the mountain at 50 metres above current sea level, high enough if—or when—the polar ice caps melt.

After an evening to get my bearings and indulge in some reindeer stew, Aquavit and Isbjørn lager, I hailed a taxi the next morning to make my 10 a.m. vault tour appointment. My hotel was only a few kilometres from the vault but walking there was out of the question. The roads were a curling rink thanks to a freak rain that had fallen the week prior. Normally, this far north in early March, Svalbard’s daily high would be about -20 Celsius. Instead, on March 4, it was a balmy -4 C.

There were no armed guards at the vault entrance, no security checks. Just three small, mangy Svalbard reindeer pawing at the ice and snow, rooting for frozen lichen and grass. My tour guide for the day, Brian Lainoff, a lanky thirty-something American, formerly the Crop Diversity Trust’s communications and partnerships coordinator, emerged with a group of potential funders from Switzerland. Eight years into its existence, securing partners with deep pockets is still a priority. As Lainoff parted ways with the Swiss he said to all of us: “It’s probably the biggest biological rescue operation ever.” Close to 940,000 seed varieties are already protected within the vault (although it’s designed to hold 4.5 million).

A glimpse in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Photograph: Crop Trust

After Lainoff bid farewell to the Swiss, we crossed a small bridge (grated to prevent snowdrifts) to the entrance. He reached into his parka for the key to unlock the massive outer metal doors. Inside, the cold seemed to hang on the curved corrugated metal lining walls of the first inner passage. The florescent lights buzzing overhead down the depth of the tunnel added a Battlestar Galactica space station feel. The steel walls became a roughly blasted shaft the further into the 134-metre tunnel we went. It also got a lot colder. The ideal conditions in which to store seeds long-term are, it turns out, -18 C and very dry. After another set of locked doors, we entered what Lainoff called “the cathedral.” We stood in front of the three storage chamber doors. “Guess which one the seeds are in,” said Lainoff, joking. It sparkled with a thick layer of frost and ice, like the inside of an old chest freezer.

The interior was like a well-ordered garage. Utilitarian wire-rack shelves filled with plastic bins, wooden crates and cardboard boxes, some barely held together with packing tape. Lainoff walked us down the aisles past boxes labelled “Canada,” “Taiwan,” “The African Rice Centre,” “United States National Plant Germplasm System.”

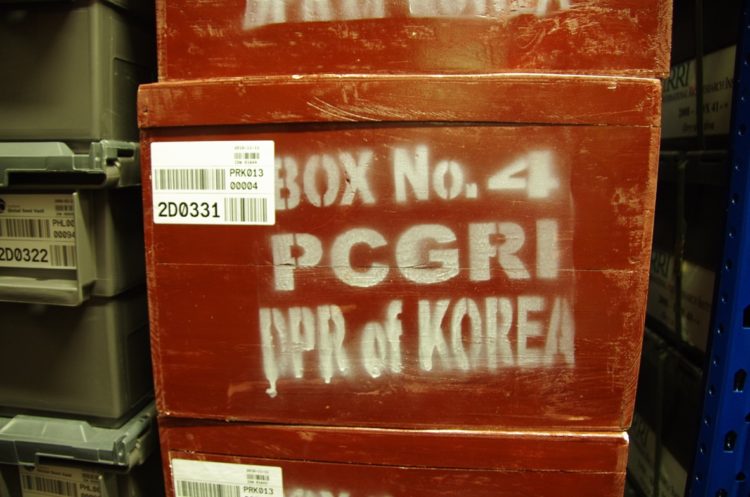

“This is a truly global effort,” he explained, “with 70-plus countries’ institutions.” This includes rare shared participation by cultural or political nemeses. Lainoff pointed to the wooden boxes, painted red with DPR of Korea, stencilled in white, like cartoon TNT crates. By coincidence, these were just steps away from blue bins from South Korea.

My fingers were numb as I added my messy scrawl to the guest book. The first name in the book was that of then UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon.

The boxes are never opened in Svalbard, as the seeds inside are the property of the depositor. Svalbard merely stores them and will extract them only if and when requested by the owners. (The boxes are scanned by X-ray for security purposes.) Most boxes are filled with dozens of seed varieties vacuum-sealed in Mylar pouches with barcodes and content labels from the depositor’s own cataloguing system.

Lainoff planted his six-foot-four frame in front of a gap on the shelves and explained that such empty spots are out of the ordinary. The seed boxes are always shelved in the chronological order in which they are received, and are not catalogued geographically. But there was a gap on the shelf because in 2020 the International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), a consortium with 32 member countries, withdrew a portion of its seed bank. ICARDA preserves unique crops of cereals, legumes and forages from some of the most agriculturally significant places in the world. During the civil war in Syria, ICARDA’s Aleppo office—once one of the most important seed repositories in the world, partly due to Syria’s historical relevance as the country in which wheat originated—had to be evacuated. Only 87 percent of the seed collection was saved. The rest was looted for the glass containers. The seeds were thrown away.

Korea’s contribution to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Photograph: Liv Dahl

Which was why ICARDA requested its seeds in 2020, so that crops could be replanted in locations in Morocco and Lebanon in order to grow them out and replenish seed stocks. Who knows if ICARDA’s seeds will be important someday, Lainoff added. Maybe they contain a resistance to a yet-to-appear wheat fungus, or maybe they have genetics that can be bred into new crops that tolerate soil salinity better. Maybe they’ll just produce the kind of better tasting, more nutritious food that has nearly been lost in the mill of mechanized, industrial scale production. Wouldn’t that be reason enough?

As Lainoff finished off this final and wholly sensible point, I noticed my teeth chattering. My fingers were numb as I added my messy scrawl to the guest book. The first name in the book was that of then UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. He wrote: “This is an inspirational symbol of peace and food security for the entire humanity.” My jet-lagged and frozen brain merely managed: “Thanks.”

We re-emerged into the blue light of the silent arctic, and I realized I was ambivalent about the stockpile of seeds I had come so far to see. Yes, climate change is confounding our farmers and their options are increasingly limited. And corporate interests will try to further enclose their ability to regulate seed sales and control seed genetics. The narrowing of the food system’s biodiversity has nations and scientists alarmed enough to stockpile seed genetics.

But is this our best option? The diversity of options for foods that could otherwise be in the hands of hundreds of nations’ farmers producing billions of breakfasts, lunches, dinners, banquets and feasts are instead locked in a melancholy Norwegian crypt. Of course, I understood that it was largely about preserving what might otherwise be lost, but it also felt somehow defeatist, to the conviviality that I love about our relationship with food.

Is a mega-seed bank at the top of the world a solution to a problem or merely all we can muster right now? These ex situ collections are, after all, just glorified warehouses built as but a partial shelter against an onslaught of larger forces. Svalbard has no control over the global climate or corporate interests, not to mention generational knowledge transfer. What good are all these seeds going to be if we lose the knowledge of when, where and how to plant them? Will future generations know how to farm them successfully? The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is, in the end, a collection of potential raw ingredients. Where are we storing the recipes?

• Jennifer Cockrall-King is author of Food and the City: Urban Agriculture and The New Food Revolution and Food Artisans of the Okanagan, and she founded the Okanagan Food and Wine Writers’ Workshop. She is working on a book a seed banks and seed savers around the world.

Thousands of seeds are locked in a frozen mountain in Norway to protect our global food supply. Should we be worried? Our writer bundles to visit the Svalbard Global Seed Vault

In a recent stroll in the woods, I came across a leafy bramble loaded with small dark fruit. Recognizing they were blackberries, I extended my arm and grabbed a handful. Moments later, I encountered a straight but flexible tree branch. I fashioned a fishing pole and dipped the hook into the nearby pond. Three quick […]

I was a third-grader when I first entered a psychiatrist’s office. The prelude to my visit was a skipping lesson I gave my brother, who was in first-grade at the time, one morning before school. Not skipping as in using a skipping rope, but the locomotive kind in which you lift your knee and hop […]

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

[…] From Issue #10, Eighteen Bridges, Spring 2020 […]