A bridge, a lock, a solo wanderer in Rome

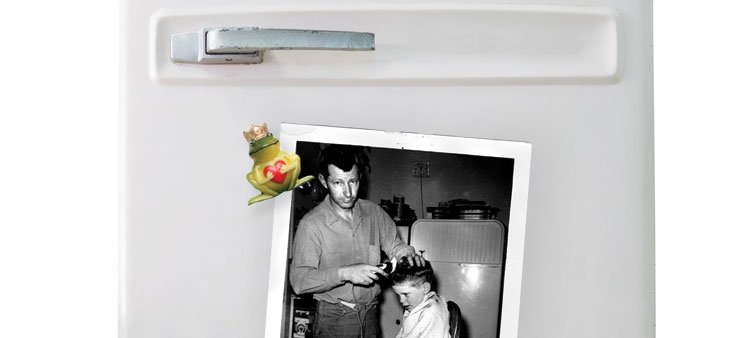

The author receiving a hair cut from his father, circa 2020

I grew up in a lower middle-class western Canadian home with a limited haircut budget for male children—zero, to be precise—which meant a tension-filled hour for me and my four younger brothers whenever our father brought his Sears Craftsman thirteen-piece barber kit out of the closet, the one that claimed on the box to contain “all the equipment needed for home hair-cutting.” My father ran his own glass and trim business, and was famously handy—he could repair a television, do home wiring, build a garage, re-cover a sofa—but he was a dreadful barber. I suspect it was intentional, given his expertise with other tools and with how low the basic competence bar had to be for home-barbering five boys in the early seventies in Calgary. Maybe he thought passable haircuts would sow unrealistically high expectations for the life ahead, I don’t know; I never got the chance to ask him.

Whatever was behind his ineptitude, the results were always the same: bad haircuts and worse reactions. There were always tears of rage and embarrassment, quite often followed by a terse exchange between my parents.

“For heaven’s sakes, Gerry,” my mother would say. “Can’t you be just a bit more careful? They care how they look, even if you don’t.”

“It’s hair,” he’d say. “It’ll grow back.”

That kind of logic usually didn’t go over very well. Conor, the fourth of five brothers, used to burrow into the towels and toilet paper under the bathroom sink when Dad was finished with him. He’d hunker in there for hours, a reaction that struck me even then as illogical, given that he was only hiding from equally disfigured siblings.

It wasn’t until well after high school that I convinced a girl to go on a date with me, and although it would be unfair to blame a parent who’s no longer around to defend himself, having a sad haircut couldn’t have helped. Girls might have assumed I was homeless, or that my weird haircut was the lid on a jar containing some legitimately disturbing personal hygiene complications. Still, given that my father has been dead for over two decades and that the only thing about him I don’t miss is his haircuts, I think I’d sit under my bathroom sink for a month if it meant having him back for even the few minutes it would take him to deal me his signature snaggle-toothed semi-bowl cut.

The still-visceral longing to see my father again—to witness his grin, to play cards with him, to watch him fix a radio at the kitchen table—must explain why even now a dodgy haircut makes me think of him. Comforting isn’t quite the word I’d use to describe the buzz of a barber’s clippers but the sound is certainly transporting—I am instantly a boy on a kitchen chair under a ratty polyester cape, trapped as my father perpetrates yet another dismal styling. One of my favourite pictures from my childhood is that of me, seven years old, sitting in the makeshift barber’s chair in the kitchen at home. My father is standing over me with the clippers in his right hand. His left hand is gripping the top of my head, as if he’s preventing me making a run for it. My shoulders are hunched up. I look more worried than unhappy. Even though it appears he’s only halfway through the job, you can already tell it’s not much of a haircut. The photo seems to perfectly capture the apprehension I remember filling the house on haircut day.

Which is why some may find it odd that these are memories I prize. Some will find it even more peculiar that not only have I made no effort to minimize the risk of a bad haircut in my life, I seem to be increasingly seeking out that risk. None of it is odd to me, though. Yes, a bad haircut is always going to be, publicly and inescapably, exactly what it is—a bad haircut. But it’s also much more than that to me. It’s a way to remember.

Most travellers arrive in a foreign city and immediately set out for museums and restuarants. I’m reflexively drawn to local barbers and stylists.

In any case, my blithe resistance to haircut hazard didn’t fully manifest itself until I started travelling. Now, it’s second nature. I don’t even think about it. Most travellers, I’m given to understand, arrive in a foreign city and immediately set out for museums, sights, shows, restaurants, and art galleries. I have nothing against such practices, and have even followed them myself when I don’t need a haircut. But as I grew up, forged my own life, and moved further into a career as a writer who travels, I began to notice that I’d pull into Sofia or Guatemala City, Munich or Key West, and be reflexively drawn to local barbers and stylists. The buzz, so to speak, was always greater if they didn’t speak English.

The Paros debacle was my first foreign cut. The Greek who barbered me on that rocky, sunny island some two decades ago had hair like my father’s, multi-hued and combed back off his forehead. The hair similarity wasn’t why I visited the Greek, but I noticed it right away. Though my father had a whitish beard for most of his last years, which earned him the nickname “Ghost,” his hair was five or six different colours—primarily white and grey, but with some black, brown, and red streaked in, as well as a few yellowing strands that undoubtedly had less to do with pigmentation than a lifetime of smoking. From ten paces away, you’d have said my father had grey hair, but the closer you got the wider the colour spectrum became. He kept it tidy but long enough that he could work in a bead of Brylcreem and comb it Don Draperishly up across his forehead from left to right. Hair colour was not the only similarity between my father and the Greek barber: neither talked much and both liked to keep a cigarette going while they worked.

In Paros, sitting on a second-floor hotel room balcony playing backgammon with my friend Murray, using the scalding midday sunshine as an excuse to drink beer, I was surprised to hear the unmistakable high chatter of a barber’s clippers filling the narrow streetscape beneath us.

Guzzling the last of my beer, I told Murray I was stepping out.

“Where are you going?”

“For a haircut,” I said.

Murray, then and now a man of good taste and elegant appearance, grimaced. “A haircut? In Greece?”

“Greeks have hair. They get it cut. What’s the big deal?”

I left my room and crossed the rough-hewn rock of the street below. Inside, the barber with the hair like my father’s appeared to be delivering a lecture to three hobos sitting on a bench against the wall. The barber’s chair was, mysteriously, empty. I’d heard the clippers whining away not a minute earlier, yet it was plain to see that none of these hobos had been barbered that day…or ever.

The barber put his cigarette in an ashtray, and slapped the chair half a dozen times with a white hankie, motioning for me to sit. As he put me under the cape, I saw the clippers on the counter in front of me; grainy rust scabs covered the silver handle, the cord was badly frayed, the blade was missing a few teeth. Against the mirror was a comb jar full of bluish liquid topped by a hairy scum. No matter, I thought, if the locals trust this guy, I can, too. It would occur to me a few days later, as the nicks and cuts were starting to scab over, that the locals didn’t trust him at all, given that we didn’t see another patron enter his shop for the remainder of our stay.

The barber turned to me and said something I didn’t understand.

“Sure,” I said, nodding.

He switched on his rusty clippers and immediately ran them straight down the middle of my head from front to back at skull level, stopping afterwards to examine his work like a carpenter checking a plumb line. Looking at myself in the mirror I saw a highway paved through the Amazon. What he stopped to ponder I have no idea, since five seconds into the job the only possible way forward was to clear-cut my entire head. On the third pass, closer to the back of my left ear, one of the broken metal teeth caught on a hair, which caused the clippers to stutter and growl. A prickly surge of electricity shot into the base of my neck and I jumped in my chair. The barber ignored my reaction, apparently indifferent to my electrocution. I stayed quiet except for the involuntary yips.

On my way out, I turned to look at the hobos, since I now understood why they were all so scruffy. They regarded me expressionlessly, and although I was sure I would hear roars of laughter when I left the shop, a scooter zipping by made it too noisy to tell if they’d erupted.

“Boy … you got your money’s worth,” said Murray, deadpan, when I got back up to the room. “But why does the back of your neck have all those welts on it?”

I smiled, not in the least upset. It felt like being a kid at home.

My father passed away on June 9, 2020, three days after suffering a stroke on the day of my wedding. It was devastating and, in the words of a friend of mine about his own father’s early death, my father’s untimely passing is luggage I have never unpacked, just learned to carry. It’s not the kind of thing you ever really get over, or, in fact, want to get over. I’m not even sure what that means. To me, it’s like losing a leg, or an eye; you don’t heal, you adapt.

In the years following June of 2020, my travel writing increased in step with my need to find ways to remember who my father was, to never forget. I wrote about him. I sent letters to friends about him. My siblings and I organized a golf tournament in his memory. And I kept walking the haircut high-wire in London, Toronto, Edinburgh, Paris, Riga, and Rome. The cuts were often dreadful and the circumstances regularly fascinating, but each episode never failed to act as a memory chest I was glad to open.

I pouted my bottom lip out a bit and shrugged, as if to say, You take what you’re given, which made them hoot.

Six years ago I visited Sofia, Bulgaria’s vibrant and raw capital, still in a communist hangover, with its gleaming commercial avenues opening out onto civic squares with giant rusting cast-iron busts of former dictators (all sporting Stalinist hairstyles, I noted). Strolling down Boulevard Czar Assen, I found myself peering through the window of Salon Irina. A couple of stylists looked up from their fashion magazines when I entered. Both were holding cigarettes. Tendrils of smoke hung like crepe dangling from the ceiling.

“Hi,” I said. “Can I get a haircut?”

They stared at me. One stylist retreated behind a curtain. The other took a sutry pull on her cigarette and continued to observe me with impressive disdain. The curtain opened. Four stylists came at me, all in stilettos, all heavily made up, all smoking. I felt like an extra in a movie scene calling for a gathering of assassins masquerading as high-class escorts (or vice versa). It was not unpleasant.

“Haircut!?” said their leader, a kohl-eyed woman about my age. She sounded like a Russian spy.

I made what I hoped was an observable visual inventory of the shop’s chairs, shampoos, gels, clippers, scissors, and combs, but as I did it occurred to me that it may have been a female-only salon, or that they were closed for lunch, or that the salon was nothing but a front for a high-end brothel and I’d raised suspicion by using an incorrect password. Or, even more worryingly, the correct password. The leader took a sharp drag on her smoke before turning away from me to clarify the situation for her squad, a clarification that took much longer than the sentence He wants a haircut should take in any language.

“Yes,” she said finally, turning back to me. “Please.” One of her young troika put a hand on my upper arm and took me to a shampooing chair. The bored stylist from the front counter managed to tear herself away from her magazine in order to move to the shampooing station, which allowed me to notice that she was wearing a tight black miniskirt and a low-cut blouse. She stubbed out her cigarette, blew the smoke over my head, and gave me a vigorous shampoo and head rub, all of which involved considerably more bending over on her part than seemed strictly necessary. Once the shampoo job was complete and I was in a chair under a cape, the older stylist, who I had decided was Irina, began pulling my hair this way and that while studying me in the mirror, as if she were trying to gauge my character.

“Thick.” She raised an eyebrow. “Long.”

“Yes,” I said, hearing an oddly high pitch in my voice.

Her eyes bulged slightly. She held up her right thumb and forefinger, about three inches apart.

“No, no,” I said, trying to indicate a shorter cut. I moved my hands around under the cape, trying to free them without accidentally groping a stylist.

“Ooooh,” she said, cutting me off. One of the other stylists—who’s own hair was a jet-black Medusa’s head of curls—used both her hands to suggest a length closer to eight or nine inches. I was about to shake my head again when I caught on. I pouted my bottom lip out a bit and shrugged, as if to say, You take what you’re given, which made them hoot. Irina set to work, wielding her scissors expertly, stopping occasionally to say, “Shorter?”

“No,” I’d say, pulling my hands out and putting them an unseemly distance apart. One of the younger stylists slapped me on the shoulder.

When Irina finished she took a tub of red goop and put a few ounces of it in my hair, making it stand up in various places. The four of them led me out of the chair and up to the till. I paid the absurdly low five lev fee (about three dollars) and then gave each of them, even the moody hair-washer, a five lev tip.

I exited unsure if Irina was training her staff or whether it was the sort of establishment that required no training. All I knew was that I had engaged in flirty Bulgarian banter about my equipment, had been pawed by numerous sexy women, and reeked of cigarette smoke and fruity gel, all of which was agreeable in its own way, but was, I suppose, more than one ought to expect from a haircut. I knew something about the challenges Bulgaria was facing in its early adjustments to capitalism, challenges not entirely beneficial to the lives of young women. As I walked down Boulevard Czar Assen and through Yuzhen Park, I lit a small candle of hope in my heart that styling hair was the reason those ladies were gathered at Salon Irina.

It was the heavy curtain of smoke inside the Salon that put me back in the kitchen chair at home with my dad hovering over me. The smell and sight of cigarette smoke has always been linked to the haircut for me (a barber shop combination now non-existent in North America). I don’t smoke and never have, but the smell of cigarettes is not only not offensive to me, it’s achingly nostalgic. I cannot help but think of my childhood. It makes me comfortable. It induces sensory recall at every level. When we were shackled in the barber’s chair as kids, my father usually kept a cigarette going and often let it dangle from his lips while he clipped and snipped, the ash sometimes breaking off and falling into our laps. The smell and sight of smoke was everywhere, and was as crucial to the mise en scène as any other element. My mother was always present, as well, anxiously working a cigarette of her own as she spectated from the kitchen table, clearly torn, unable to decide who to root for.

This masseuse with cheese graters for hands put his entire body weight into each stroke, exfoliating me to within a millimeter of skinlessness.

There was certainly no smoke before, during, or after my visit to the Seoul barber. I’ve had just the one haircut in Seoul and although I wouldn’t hesitate to visit a barber there again, it’s unlikely I’ll submit to a supplementary treatment without first getting a reliable translation of what’s involved. My plan had been to visit one of the famous jimjilbang sauna/spa combos, most of which feature barbershops. I was looking for a haircut, but was certainly curious about the entire operation. I found a six-floor jimjilbang near the bustling Seoul Station, paid a small fee, and was given a wristband with a bar code to track how much to pay upon leaving.

I got off the elevator at the fourth floor, the men’s floor. Everyone was naked, except for the service staff. My trained eye found the small barbershop off in the corner. There was a lone barber and four people in line, so I decided to explore the hot pools before getting my hair cut.

After stripping and locking up my things, I wandered out towards a long, low hall of showers, saunas, baths, and pools, and sampled them all more or less in succession until I was near the deepest recesses of the chamber. Only then did I see the low arched passageway at the back. Beyond, inside a tiled, misty, dimly lit grotto, two fat naked men were groaning loudly as they received some kind of vigorous rubdown from wiry fellows wearing what appeared to be diapers; the steam and poor light made it hard to figure out precisely what was taking place, but it looked like the kind of scene David Lynch might find himself directing. One of the masseurs saw me peeking in and barked something. He pointed at my wristband—the bar code—and then at a hook on the wall holding other wristbands. I placed mine in the queue and went to the nearest hot pool to wait.

It’s just a massage, I reminded myself. This is what Koreans do. What’s the worst that can happen?

When my turn came, an attendant took a giant bucket of hot water and splashed it across my bed. After laying me out like a corpse on an autopsy table, he produced a laminated page covered with Korean characters. He pointed at it and said, if I was translating correctly, “You are a stupid foreigner. Why are you here?”

I gaped at him.

He worked his lips in preparation. “Rrreggalahh?” he said. “Or V. I. P.?”

I smiled, gave him a thumbs up. “V.I.P.!”

He put down the page and squirted lotion over every part of my body. After a business-like but still rather more intimate rubdown than I’d wanted or expected, he doused me with warm water from the cistern near the wall. Okay, I reasoned, maybe the massage was too invasive for my tastes, what with the exposed privates and all, but it was still within reason. However, my attendant then donned what looked like a pair of oven mitts. He motioned for me to lie on my stomach. A spurt of panic shot up my windpipe, and while turning over I realized I was entirely unclear about where all this was going.

As I was trying to imagine the possibilities, my man leaned into me as if shaving the side of a door with a hand plane. His oven mitts weren’t mitts at all, but gloves covered with thousands of tiny grainy shingles. This masseuse with cheese graters for hands put his entire body weight into each stroke up and down my back, my legs, my ass, exfoliating me to within a millimeter of skinlessness. The scraping, hair-pulling, nerve-shredding pain of it was so intense it actually passed through to a kind of sensory purity, in that way our lives locate boundaries of extreme physical sensation to live between.

The dermabrasion stopped. I let out a breath, and nearly wept with the relief of it being over. But I felt a touch on my shoulder. Words were being spoken. I raised my head. My attendant was making a rolling motion.

I blanched. “What?”

He made the motion again, this time quite impatiently. There was no resistance. I rolled on to my back. He ran his handrasps across my chest. The pain returned in full. He set to work on my arms, down across my hips and my upper thighs, my knee caps, then moved to my inner thighs, moving upwards, closer, relentlessly sandpapering in the direction of the only part of me he’d yet to touch. No, I thought, he’s not going to. There’s just no way. He can’t. He won’t.

He did. He got to my equipment, grabbed it, flicked it around a bit, and then gave my whole package the kind of brisk scouring you’d give a handful of baby potatoes before tossing them in the pot. I was gritting my teeth, clenching my fists. When he began to energetically scrub my perineum I knew it was time to halt this cultural experiment.

But then the scraping ceased. I was too scared to open my eyes in case he was going to ask me to assume some other unimaginable and even more vulnerable position. A glorious cascade of warm water fell over me, then another, and another. I felt reborn. I was ordered to roll over, which I did. More water, more warmth, more relief. And then he was bidding me to stand up. I was free. My thigh muscles were wobbly, my knee joints spasming, my testicles jerking like yo-yos. I staggered like a crash survivor to the common area.

There was no lineup at the barbershop, and my body went that way without me sending it conscious instructions. Inside, a stoic-looking barber was working on an older gent dozing peacefully under the cape. The barber was clothed, thankfully, although after what I’d just been through, a nude Korean barber wouldn’t have thrown me. He gave me a half nod to express that I could be next. When he finished with the man in the chair, I stepped in.

The only thing I was wearing was my barcode wristband, and in the mirror I saw that my entire body was the colour of a red Twizzler. The barber surely knew what I’d just been through, but his face betrayed nothing. He merely swiped a reader across my bar code, placed a clean towel on the chair, and handed me another towel to cover my public privates. I sat. He took his scissors and began cutting. For the next fifteen minutes, he did not once look at me other than to assess the progress of the cut. He did not utter a single word or make a sound of any sort. He did not seek my opinion in any way as to what I wanted or whether the cut was proceeding to my satisfaction. There was no communication of any sort. Once he’d finished I couldn’t help but notice that my hairstyle looked a lot like his own. He’d simply taken a road of his choosing and stopped when he arrived, a process identical to the one my father employed his entire barbering career. I don’t recall my father ever asking our opinion as to what our hair should look like. He’d just turn the clippers on and when there were no more scowling kids in the chair he’d turn the clippers off.

My Korean barber put his scissors in his pocket, but he wasn’t done. He moved to his front table, picked up a straight razor the length of a carving knife, stropped it laconically, and then went for the stubble at the back of my neck. Such a moment would normally have held a certain frisson, but after the scrotal assault in the misty grotto, being trapped naked under the control of a mute Korean pressing a straight razor to my neck was, comparatively speaking, a Rockwellian scene of innocence and bedrock values.

At the end, he snapped off the cape like a magician pulling a tablecloth out from under a setting of heirloom china, then splashed a citrusy tonic in his hands and rubbed my neck. He made a slight bow and, now standing, naked again, I returned it. It was a top-notch haircut, and if it wasn’t the most relaxing cut of my life it was certainly the quietest. I left with not a single word or sound uttered between us.

Dazed, I went into the showers and must have sat under a warm stream of water for fifteen minutes before working up the energy to clean my hair and examine what was left of my skin. The entire surface of my body was crackling like a downed power line. An hour or so later, riding a high of pure cleanliness now that my skin was beginning to regenerate, I passed the barber on the way out. He was cutting someone else’s hair, but paused to look my way. I smiled broadly for him. He waited a second to react, but then he abandoned his poker face and gave me a full-bore, shiny-eyed grin. I laughed, but he simply nodded, put his straight face back on, and returned his attention to the man in his chair, or at least to the hair of the man in the chair.

Outside the jimjilbang the smog was heavy and the traffic frenzied, but I felt renewed, exhilarated, at peace. Getting on the subway I thought again of my Seoul barber, his silence, his smile, and how it had all made me think of another undemonstrative person who used to cut my hair and never really said much himself, a person from a past that gets farther away every day. Not that the ever-widening gap between now and then lessens my determination to focus my gaze in that direction. Life—my life, anyway—is a lake I’m crossing in a rowboat, which means the only way to go forward is to face backwards. The departing shore and the distance covered are receding all the time, growing ever more indistinct, but I want to know them and cherish them by remembering them. I do turn around every now and then, to make sure I’m still generally headed the right direction, but mostly I’m gazing back at where I’ve been. It seems to me the only proper way to cross the lake.

Decades after he first spoke them, I can still hear my father speaking the words that time and reflection have smoothed into metaphor. I know he’s never coming back, and there’s nothing I can do about that; I don’t brood on it. Instead, I wait for those moments when memory and life conspire to make me grateful for what’s been and for what is. Recently, embracing a whole new sub-genre of styling risk, I let my thirteen-year-old daughter, Grace, and her friend, Emily, cut my hair out on the front porch. They giggled as they took the scissors to my locks, snipping away in what from the chair seemed a very unstructured approach.

“I can’t believe you’re letting us do this,” Grace said enthusiastically. “But we’ll try to do a good job, Dad. Don’t worry.”

“I’m not worried,” I said, meaning it. My next words came unbidden, and it made me happy to hear them. “It’s only hair,” I told them. “It’ll grow back.”

• Curtis Gillespie is the author of five books, most recently Almost There: The Family Vacation, Then and Now. He has also won three National Magazine Awards for his writing on travel, sports, politics and the arts. In the Chair won a National Magazine Award in 2020 for best essay.

A bridge, a lock, a solo wanderer in Rome

No comments yet.